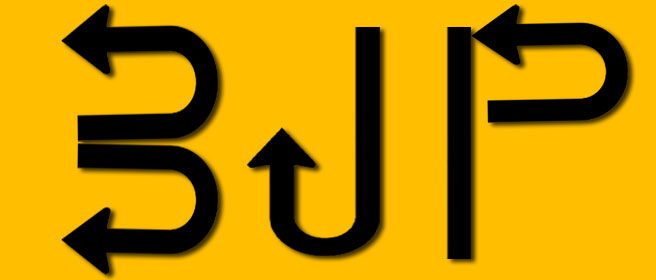

A Government Of U-Turns (Part 1 – The India-Bangladesh Land Swap Deal)

The history behind the India-Bangladesh land deal and how the BJP flip-flopped on the issue.

It was a time of great upheaval but one wouldn’t have known it. Indian history is a place where myth often intertwines with reality and of little consequence – to the protagonists or the historians – is the cost borne by later generations. The Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi addressed one such consequence last Sunday, when he talked in favour of the India-Bangladesh land swap deal signed by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2011. That it was a U-turn by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) we’ll get to later. First the history.

One fine day 300 years ago, the Maharaja of Cooch Behar – a kingdom nestled in the Himalayan foothills of Bengal – decided to play chess with the Faujdar of Rangpur (now in Bangladesh). In keeping with the innate principles of debauchery, they decided also to bet on the outcome, using the villages under their rule as currency. A pull of the hookah, a King’s Indian defence, and a village lost forever. The riveting 2002 research paper, Waiting for the Esquimo: an historical and documentary study of the Cooch Behar enclaves of India and Bangladesh, by Brendan Whyte, is a definitive 519-page account of these “chess lands” or enclaves. Austria, Italy and Germany have 1 enclave each. India and Bangladesh in comparison have a combined total of 254. The history of these enclaves has as much to do with chess games as it does with the history of the kingdom of Cooch Behar, that fought the Mughals until the force became too much to counter. A treaty was signed in 1713 between the Maharaja of Cooch Behar and the Mughals, delineating the enclaves or chaklas as they were called. Waiting quietly on the sidelines and ready to pounce were the trusty British. The East India Company, founded in 1599, had been crawling inwards leisurely, imperious its design, insatiable its greed. The decline of the Mughal Empire in the mid-18th century allowed the British the one chance they had been waiting for. And they took it. Spectacularly.

In 1756, when the Nawab of Bengal Siraj-ud-Daula wrested Calcutta from the East India Company, little did he know he was about to change the course of Indian history. The captured Brits were rounded up and thrown in a clanger that came to be known as the infamous Black Hole of Calcutta. News reached the irascible Robert Clive who set sail for Calcutta at once. He met Siraj-ud-Daula on the banks of the mighty Bhagirathi. The place was Palashi and the year 1757. Less than a thousand Brits defeated one of the largest armies ever assembled in the subcontinent to counter them, totalling more than 60,000. Yes – 60,000 professional troops and one Gaddar-e-Abrar, Mir Jafar Ali Khan.

The victorious British, after appointing Jafar as the new Nawab of Bengal, then began – as was their habit – a systematic survey of all the “chess lands”, and by 1773 the boundaries between Cooch Behar and the East India Company were fixed for posterity and sealed with a treaty that, among other gloriously sly windfalls, promised to the British the “subjection of the Raja of Cooch Behar to the English East India Company”, allowance for Cooch Behar “to be annexed to the Province of Bengal”, and an agreement to “make over the English East India Company one-half of the annual revenue of Cooch Behar for ever.”

Complaining about the media is easy and often justified. But hey, it’s the model that’s flawed.

Pay to keep news free and help make media independent

Exactly 100 years from the Great Battle of Plassey, almost to the day, came the Mutiny of 1857. Through a little bit of daring and a whole lot of cunning the British won that too, and to rub salt into our wounds the British crown took over the reigns from the East India Company. Enclaves began to be let, demarcated, and transferred on someone else’s whims but not before they were – again by way of habit – scrupulously notified, as was the case on September 13, 1876 when, through The Calcutta Gazette, one came to know that 19 villages of Dinajpur had suddenly been transferred to the district of Rangpur. The land transfer and appropriation game continued unabated until 1905, when the pastime reached an altogether higher level. Bengal was divided. Enclave-ridden districts such as Rangpur and Jalpaiguri now came under the East Bengal province (that included Assam) while Cooch Behar went to Bengal. The division resulted in a Hindu majority (in Bengal) and a Muslim majority (in East Bengal & Assam). Bengal erupted. Vande Mataram was on every Bengali’s lips. Fearing a mass uprising, the British reorganised Bengal in 1912. Assam was given separate status as were Bihar and Orissa. Cooch Behar once again found itself firmly entrenched from all sides, with Assam forming the new boundary on the right. We’ve had enough of this, the Brits must have thought, for they moved their capital to Delhi the same year, leaving Bengal to deal with the legacy of land disputes.

Fast-forward another 40 years and it was time for the Brits to embrace constant drizzle once and for all. But not before a certain Lord Radcliffe was handed the task of dividing India. His befuddling lines of chalk soon turned into rivers of blood. A firm hand and a wise head was needed to deal with the horrors and it came in the form of the Iron Man of India. In little more than six months, Sardar Patel persuaded 600 kingdoms and principalities to unite and form one nation under heaven. One such kingdom was Cooch Behar whose Maharaja gladly signed the accession papers. Fifty enclaves came along, 200 were left behind, leading to a confused population not knowing which flag they now came under. Bloodshed continued. The Congress Chief Minister of Bengal, BC Roy, asked Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to allow for religion-based exchange of population along the turbulent Radcliffe Line. Nehru refused. The boundary issue has remained unresolved ever since, despite a serious effort by both sides in 1958, an effort that was fervently opposed by the Hindu Mahasabha, the progenitor of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and the BJP.

This seemingly intractable legacy, of chess games and treachery and criss-crossing lines and bloodshed, was finally addressed in great seriousness by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his Bangladeshi counterpart Sheikh Hasina in 2011. The so-called Dhaka Agreement entailed the swapping of 111 Indian enclaves that are part of Bangladesh, for 51 Bangladeshi enclaves that are part of India. India, with 17,000 acres of Bangladeshi enclaves, stood to lose 10,000 acres of its land if the swap materialised, as Bangladesh has 7000 acres of Indian enclaves. Although a welcome step, the land swap would have been nothing short of Alice making sense of her Wonderland. The words of one reporter illuminate the task at hand: “A few years ago, away from Cooch Behar, on the eastern border with India, I met a man who lived smack on the border between Tripura state and Bangladesh. His living room was in Bangladesh, his toilet in India. He had been a local politician in India, and was now working as a farmer in Bangladesh. As is typical in such places, he sent his daughters to school in Bangladesh, and his sons to India, where schools, he thought, were much better.”

In Parliament, when the UPA government was asked pointed questions on the Dhaka Agreement, it replied that the agreement was “based on the situation on the ground, takes into account the wishes of the people residing in the areas involved and was prepared in close consultation with the State Governments concerned, including the Government of Assam. The national interest has been protected.”

But the agreement didn’t go down well with a few political parties. These were, in alphabetical order, Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), Bharatiya Janata Party and Trinamool Congress (TMC). Within weeks, the BJP produced a resolution. “The BJP National Executive,” said the resolution, “notes with concern that the India-Bangladesh Land Transfer Agreement reached in Dhaka has ignored the feelings and sentiments of the people of the border States of Assam and West Bengal…While the BJP is in favour of improving ties with Bangladesh and appreciates the present Government in Dhaka for the steps it has taken to curb activities of separatists operating from there, this cannot be at the cost of the livelihood and properties of Indian citizens living in the affected border regions. The BJP is of the view that the demographic invasion of India by illegal Bangladeshi migrants has already severely affected the identity, culture and social cohesion of many parts of Assam and West Bengal. No further compromise with the country’s national interests can be permitted.”

What the BJP conveniently overlooked was that the Dhaka Agreement contained minute details of how the swap would take place and where the demarcations would lie. This wasn’t a Radcliffe redux. These mind-numbing details had been arrived at after 30 years of fussy drafting post the 1974 Indira-Mujib pact between India and the newly-formed Bangladesh. The agreement wasn’t written in a hurry or at the “cost of the livelihood and properties of Indian citizens living in the affected border regions.” What was written in a hurry was the BJP resolution, claiming that everyone from the Indian security forces to the Indian farmers are “in the dark”, and providing just one example by way of evidence, that of Chandannagar, a village in Tripura: “Some land near Chandannagar is scheduled to be transformed which is being opposed by the settled population of Indian there.”

Indeed, Chandannagar had been in the news in the context of the India-Bangladesh land dispute, but in 1984 not 2012, when the government of India decided to transfer Chandannagar – with a population of 338 – to Bangladesh. On the other hand, the 2011 Dhaka Agreement only talks of boundary demarcation in Chandannagar: “The boundary shall be drawn along Sonaraichhera River from existing Boundary Pillar No 1904 to Boundary Pillar No 1905 as surveyed jointly and agreed in July 2011.”

BJP’s other contention, about survey maps not being in public domain was nit-picking, nothing more. The Department of Science and Technology routinely conducts India-Bangladesh border surveys and catalogues them meticulously. Indeed, a month before the Dhaka Agreement, 1149 survey maps were jointly signed by the two countries. And as the agreement itself mentions, the enclaves were to be swapped keeping in mind the survey maps that were looked at and exchanged as far back as in 1997.

Lest one forget, between 1998 and 2011 the BJP government was in power for 6 years – a period during which it might not only have seen most of these survey maps but also commissioned the surveys.

But the BJP was in no mood to listen and in the AGP and TMC they found eager well-rushers. “The deal is nothing but an act of betrayal. We shall not allow an inch of Assam’s land to be handed over to Bangladesh,” said Chandra Mohan Patowary, the AGP president. “We shall lobby in Parliament to ensure the land pact is not implemented,” cried Siddharth Bhattacharya of the BJP. All hell broke loose in Assam. The matter reached court through a Public Interest Litigation (PIL). In 2012, in a landmark judgment, the Gauhati High Court ruled that the Dhaka Agreement could only be realised through a constitutional amendment.

In a rare display of providing a voice to the thousands affected by the cruel vagaries of our history, from Bengal to Assam to Meghalaya and Tripura, Dr Manmohan Singh decided to amend the Constitution of India to realise the land swap deal. In 2013, his government brought the Constitution (One Hundred and Nineteenth Amendment) Bill, that proposed “to amend the First Schedule of the Constitution, for the purpose of giving effect to the acquiring of territories by India and transfer of territories to Bangladesh through the retaining of adverse possession and exchange of enclaves, in pursuance of the Agreement of 1974 and its Protocol entered between the Governments of India and Bangladesh.” It is a remarkable document, a treasure-trove of strange names and places and boundary distances and land acreage. No effort was spared in detailing the mechanisms through which the land swaps are to take place. It also discloses how each and every demarcation has been the result of painful negotiations and conferences between the two countries over decades. Joint conferences, Joint field inspections, Joint ground verifications, Joint pacts – they are all there, together with the years and the dates they were held on. Anoraks would do anything to get their twitchy hands on this document.

Unfortunately, when the bill was about to be tabled before the houses of Parliament, the troika of BJP, AGP and TMC came out all guns blazing. One BJP MP, Bijoya Chakraborty, alleged that the UPA was trying to “introduce the bill to woo the minority voters.” In a desperate attempt, Manmohan Singh met senior BJP leaders LK Advani, Arun Jaitley and Sushma Swaraj, in order to seek their support for the bill. He was unsuccessful. The bill was never passed.

Last Sunday, Manmohan Singh must have heard Prime Minister Narendra Modi wax eloquent on the same Indo-Bangladesh land swap agreement. He must have seen Mr Modi being presented with the traditional Assamese Japi by the smiling Siddharth Bhattacharya who once vehemently opposed the agreement. Speechless, he must have switched off the TV in disgust and picked up the newspaper, hoping to find his bête noire still opposed to the land swap. Turning over the front page our ex-Prime Minister must have read the following: Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that his government would go ahead with a land transfer deal with Bangladesh keeping illegal influx and Assam’s long-term security interests in mind. “The land swap deal will be beneficial. It might seem to be an immediate loss for Assam, but it will serve security interests in the long term and help solve the problem of Bangladeshi migrants.”

A day after Mr Modi said his government would go ahead with the land transfer deal, the all-party standing committee (that includes many BJP MPs) to which the rejected bill was referred back in 2013, recommended that it be presented to the Parliament immediately. Crucially, no changes were sought in the number of enclaves to be exchanged. “After extensive consultations,” said the standing committee, “both India and Bangladesh have resolved the aforementioned outstanding issues by signing the 2011 Protocol…The Committee is of the strong opinion that the Constitution (One Hundred and Nineteenth Amendment) Bill, 2013 is in the overall national interest. The Committee is of a considered opinion that delays in the passage of the Bill have needlessly contributed to the perpetuation of a huge humanitarian crisis”. Soon after, the BJP spokesperson Siddharth Singh admitted in a television debate: “Our U-turns are positive U-turns.” He couldn’t have put it better. It is indeed a U-turn and it is indeed a positive one. There is no shame in his party acknowledging it so. But they would never.

Granted, our political parties are hardly the epitome of ethics and bipartisanship. Those in power realise this as much as those who are presently in opposition. But when national interest is at stake, only the gullible would allow the politician to play a game of chess, for it is dangerous beyond immediate realisation. This is because unlike the erstwhile Maharajas of Cooch Behar, what is wagered here is not land but, rather, an entity much more precious – time.

*****

This is the first in a series of articles exploring the present government’s U-turns. Next up – The Henderson-Brooks U-turn.

This article first appeared in newslaundry on Dec. 03, 2014.